Editor’s note: This guest post by Xiaoqi Chen (Princeton University) describes a queue analytics data structure implemented using P4. It is based on a paper originally published at ACM CoNEXT’19.

Queuing and Microbursts

Excessive queueing in network switches leads to higher delay and possibly packet drops. In particular, Microbursts are a phenomenon where the queue suddenly grows in a short period of time (a few milliseconds or sub-millisecond), exhausting the queuing buffer. These variations of queue length happen on a very small time scale, and conventional network-monitoring tools often cannot detect them based on packet sampling or averaged statistics, let alone localize the root cause.

Therefore, we designed ConQuest, a queue-analysis data structure that runs entirely in the data plane of programmable switches, to monitor the flows entering a port’s queue in real time, and report if any flow’s packets occupy a significant fraction of queuing buffer space. When some abnormal flows are bursting too many packets into the queue, a ConQuest-enabled programmable switch can swiftly take action on those flows to mitigate the deteriorating queueing delay and avoid running out of queuing buffer, for example by dropping, de-prioritizing, or re-routing those flows.

Estimating flow size: Round-Robin Snapshots

Today’s high-speed programmable switches impose strict restrictions on data-plane memory access, in order to maintain a high packet-processing rate. In particular, ConQuest cannot update the same data structure both when a packet enters the queue and when it exits the queue. Therefore, we cannot use the most straightforward solution where we maintain a table of flow size counters, increment them when a packet enters the queue, and decrement when it exits.

To fit into the data plane’s memory access constraint, ConQuest splits the traffic into smaller, fixed-length time epochs, based on the time when a packet departs from the queue, and uses round-robin snapshots to record the traffic in each epoch. By aggregating a variable number of recent snapshots based on current queue length, ConQuest can estimate the size of each flow in the queue, and decide if any of them is occupying a significant fraction of the queueing buffer. Furthermore, outdated snapshots are also cleaned and recycled automatically in the data plane, as the epochs are much shorter than how fast the control plane can react.

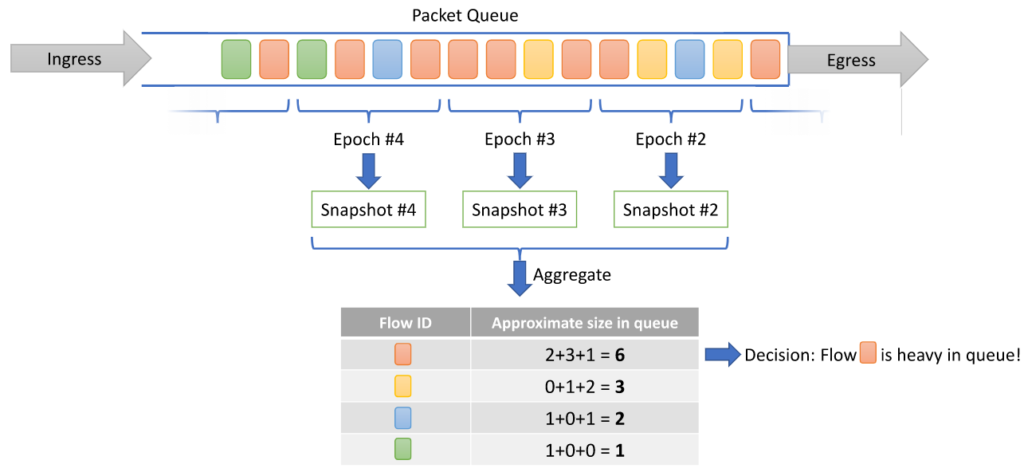

Figure 1. Each snapshot records a fraction of traffic in the queue.

We illustrate the epoch and snapshot aggregation process in the above example, where we assume a simplified switch output port has only one First-In, First-Out (FIFO) queue between packet ingress and egress, and all packets have size 1. In the example, we use snapshot epoch size of four packets; each snapshot therefore records the size of flows within its corresponding four packets. Dividing the queue length (15) by 4, we get 3, which means we should aggregate three recent snapshots to estimate the size of each flow in the queue. When the queue is shorter, we can read from fewer snapshots, and vice versa.

ConQuest naturally fits into the programming primitives provided in P4, using only the basic language primitives:

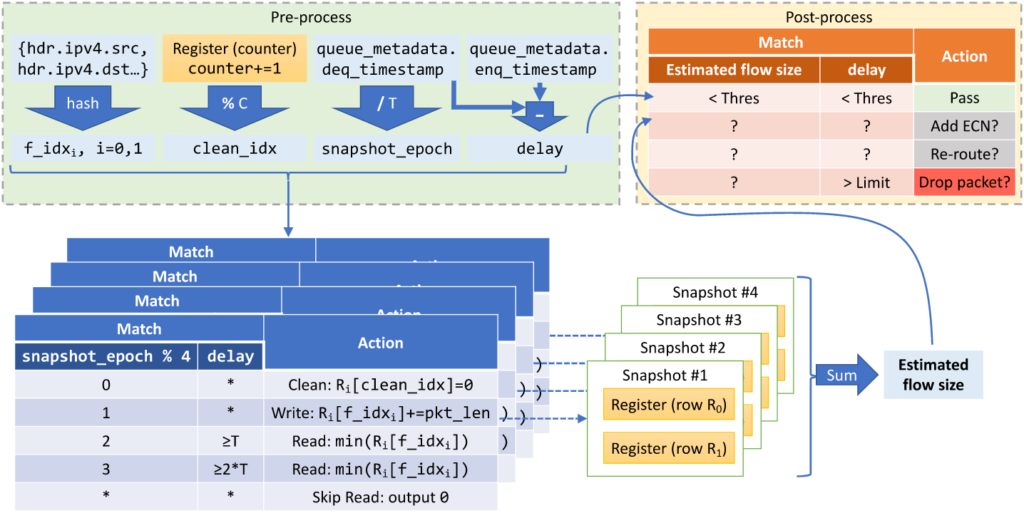

- First, we divide a packet’s dequeue timestamp by the size of each epoch, and the division can be implemented using bit right-shift (we use an epoch size that is an integer power of two, e.g., 1024 microseconds). We also subtract the enqueue timestamp from the dequeue timestamp, both available as queuing metadata, to get the queuing delay experienced by the packet.

- Each snapshot implements a two-row count-min sketch, which is an approximate data structure that supports recording packets of different flows, and later estimates the total size of each flow given its flow ID. We implement each count-min sketch using two register arrays. When a packet arrives, we extract its header fields to obtain its flow ID (e.g., the 5-tuple), then use two hash functions to get two indices. To insert the packet into the snapshot, we increment the values stored in the respective indices in the two register arrays. To estimate a flow’s total size stored in this snapshot, we read from the two indices, then choose the minimum out of the two values.

- We also prepare another index for cyclically cleaning the snapshots. To progressively clean a snapshot, we simply write zero to the cyclic index for each packet.

- Then, we use the current epoch modulus by the number of total snapshots (four in our example), to decide the role of each snapshot; if we choose the total number of snapshots as an integer power of two, such as 4, the modulus can be implemented by choosing the least significant binary bits of the epoch. In P4, we write it as variable slicing: metadata.snapshot_epoch[2:0]. As time goes by, the snapshot is first cleaned, then written, and finally read. A match-action table decides the role of each snapshot, as well as how many snapshots to read from (using range match) — recall that we divide the queue length by snapshot epoch size to decide how many snapshots to aggregate.

- Finally, the read results are added together to obtain the estimated flow size in the queue for this packet’s flow ID. A match-action table can then match on the current queuing delay and this flow’s estimated size, to take various actions (like adding ECN mark) for the bursting flows. We can implement many sophisticated queue management logic here.

We illustrate the entire P4 program’s logic in the figure below.

Figure 2. Implementing ConQuest logic using match-action tables.

Evaluating ConQuest

To evaluate ConQuest, we build a testbed experiment where bursty flows are injected into small-sized workload flows. ConQuest tries to detect and throttle these flows by adding the Early Congestion Notification (ECN) flag to the packets, and helps the workload flows achieve lower flow completion time compared with a traditional setup, where all flows are indiscriminately throttled once the queue length reaches certain threshold.

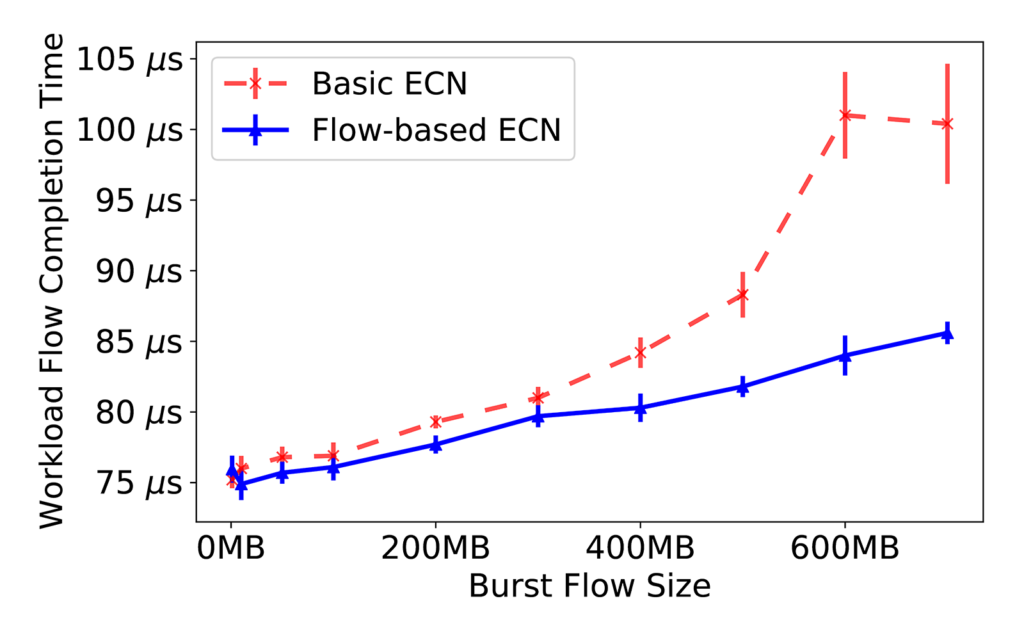

Figure 3. Flow-based ECN improves flow completion time in the presence of bursty flows.

As shown in the figure above, when the size of the injected bursty flow grows larger, the median Flow Completion Time of the workload flows also grows significantly, when the switch indiscriminately throttles all flows upon congestion. Using ConQuest’s estimates, the switch can selectively throttle only the bursty flows when the queue is congested, reducing the Flow Completion Time by as much as 11%.

We also performed various other experiments to see if ConQuest can accurately identify bursty flows, both under trace-based simulation and in real-world testbeds.

ConQuest in production networks

P4 switches are not yet widely deployed in production networks, but network operators still desire better queuing analysis. Therefore, we also proposed a novel tapping-based deployment, in which ConQuest receives mirrored traffic from a legacy, non-programmable network device and performs queueing analysis. The caveat is, ConQuest sees both the legacy device’s ingress and egress traffic, and matches the same packet’s two appearances to calculate its queuing delay, before performing the same queuing analysis.

We have deployed ConQuest under this tapping setup in two separate production networks. At Princeton University under the P4Campus initiative, we used ConQuest to debug queuing anomaly in a border router. At AT&T, we used ConQuest to monitor and analyze the characteristics of microbursts in the carrier core network. Both results have been presented in the Buffer Sizing Workshop.

Conclusion

ConQuest is a P4-based, flow-level queue analysis data structure that works entirely in the data plane. ConQuest’s implementation uses match-action tables heavily, to implement its core logic, the round-robin snapshots. ConQuest enables a programmable switch to analyze and react to microbursts and other queuing anomalies in real time, and can also be used to analyze queuing in legacy, non-programmable network devices.

Please refer to our paper for more detail about the design, evaluation, and deployment of ConQuest. Also, we have open-sourced ConQuest’s P4 code on GitHub, please check it out!